|

Doing

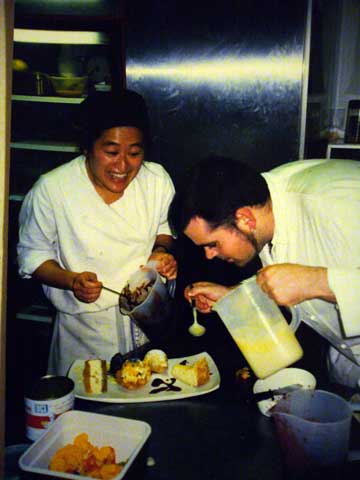

The Dishes in County Kerry Part II: Ireland, 1998 After my three-week waitressing career sank like a lead meringue I found myself out in the drizzling rain looking for a new job, and more pressingly, a new place to sleep. Kenmare suddenly took on a grey, miserable pallor, a trick of the brain when life takes an awkward turn. Bummer. I was still frazzled by being fired, though it wasn't the first time in my life. I argued that really, I never wanted to be a waitress; it was just a way to possibly get into the kitchen to do what I really wanted to do: learn to cook. I woke at 6am after a fitful night digesting my last supper, which I had brazenly chosen to take place at my former place of employment the same day I was fired. I chose the hand rolled tortellini in a tomato olive sauce followed by a perfectly executed lemon tart - neither too sweet or too sour, with a light, feathery creaminess not unlike an expensive beauty cream that comes in a fancy frosted jar. Sadly but not surprisingly, the meal did not sit well in my stomach. So first things first: a new job. I went from door to door asking for a chance to work in the kitchen. I do believe the openness and directness of Aussies makes them quite lousy bullshitters, so I opted for the honesty approach, explaining that though I had no qualifications or experience, my all-consuming passion for the preparation and execution of fine food would make me an asset to their business. The responses were predictably cool; the Irish are masters of indirectness and beating about the bush so the cultural combination between Me and Them was like chilled lard and iced water.  Assembling the triple bypass, sorry, Dessert Taster plate. "You should be able to turn that around in under 2 minutes," said sous chef Tommy. The Square Pint pub sported a self-consciously hip upstairs eaterie called Café Indigo, complete with curvy chrome and glass and dark blue effects, plus artsy duotone shots of young girls in various states of fully clothedness (remember this is Ireland) and a menu designed for nibbling and being seen rather than being seen to nibble. The starched sous chef informed me that there may be a place coming up in the glass polishing department. Darcey's, the only restaurant in town with a provisional Michelin Star was closed when I visited, but I was told that unless you'd done the hard yards at catering school you would not even make it past the 'Please Wait to Be Seated' sign. Trudge, trudge. The spry owner of the Purple Heather, a place for excellent soup and sandwich regarded me through her square spectacles. "You should try Bruce across the road…he does oriental food". (For the uninitiated reader, I have a Chinese face). Bruce was an anomoly in the staid environs of Kenmare. At 23, he'd stirred up a reputation for inventive fusion food in his restaurant and namesake, Mulcahy's Restaurant and Bar. Bruce exuded big city ambition, had travelled to far flung places like Australia, Japan, France and the States where he'd devoured the local culinary culture and returned, determined to break the moldy old mold, brazenly combining a little bit of here with a little bit of there, yet interestingly, retaining something of the flavour of Ireland. Conversely, his Irish classics were presented with an avante-garde twist, like his rich Irish Stew served on the centre of the plate with four small boiled potatoes at each compass point. I went across to Mulcahy's all ready to confess that my handle on Oriental food was as good as my steam calliope tuning prowess, but it wasn't an issue. The issue was that he had a full quota of kitchen staff, a sous (second) chef, and a very, very small kitchen. I looked him straight in the eye and told him I would work three days a week for free and get a job elsewhere in the town for money, and that I would be an asset to his business as long as he taught me everything he knew. He said to me, "I'll give you a full time job". Thus by 11.30am I had the promise of a full-time traineeship at Mulcahy's Restaurant and Bar for an as yet undisclosed paltry sum, and by 2pm, after scribbling down a phone number displayed in the post office window, I'd paid a deposit on a new place to sleep, sharing a cottage with a couple for 30 quid a week. Anna, a friend who lived outside of town, helped me move a few things to my new abode with her car. We folded my bicycle, put it in the trunk, and drove to her house to spend the night there. Her house is a delightfully higgelty-piggelty cottage perched on the side of a mountain, 15 miles outside Kenmare in a place called Lauragh on the Beara Peninsula. The garden is a riot of raspberry, redcurrant and blackcurrent bushes interspersed by free-spirited potato plants, herbs, flowers and other vegetables. The cottage is daubed white and the windows painted a cheery yellow. The living area is alive with plants and the accoutrement of active minds, young and not so young - cassette tapes, books, files bursting with clippings, framed photographs and small toys neatly compartmentalised into yoghurt containers by Ciaron, her exuberant 6 year old boy. A ladder leads to a sunlit loft housing Anna's bed and Ciaron's nook. I sat in a chair feeling drained. "You've had a big shock" she comforted, referring to the events of the last two days. I helped her cook a Hari-Krishna style curry with home grown vegetables, boosted by a generous dollop of Pataks Ginger Pickle, which I had ferried all the way from Dublin. It was comforting, and a little odd, to feel completely safe. I slept long and deep for the first time since arriving in Kenmare just on a month and a half ago. ~ I woke at 11am to the sound of Ciaron's piping voice in the loft upstairs, and went into the kitchen to make fresh raspberry pancakes for brunch. After a few games of Mastermind with Ciaron we mounted Anna's and Ciaron's bikes on the back of the car and drove down the dirt road past Glanmore Lake. Ciaron and I spent a very pleasant afternoon riding back along the dirt track whilst Anna drove on ahead to meet us. She dropped me off at the Tuosist turnoff and I rode back to Kenmare. The 16 kilometers took a mere 45 minutes, a flat, fast road. Kenmare is a small town. It seemed that everyone knew of my dismissal and were divided into two camps - those that ignored me and whispered behind my back, and those that were openly consoling. One of the latter camp was Phillipe, a well-heeled, 18 year old adopted Chinese Irish lad who waitered in the Bean and Leaf internet café. At half my age but more than fifty times my wealth he insisted on treating me to blini's (small pancakes) in Café Indigo. This time I did not decline. ~ Sunday. My last day of freedom before commencing my self-inflicted of culinary slavery at Mulcahy's. Today I managed to muscle in on an exclusive Kenmare Walking Club jaunt to Rabach's Cave, back down the road on the Beara Peninsula near Anna's place. I called up the local primary school principal and club stalwart Donal O'Sullivan to arrange a lift to the striding-off point. The walk turned out to be a pleasant if boggy two hour ramble into a capacious valley. Denise, supermum, brought her four young ones including a six-week old babe-in-sling. She'd never missed a hike, apparently. Rabach was a family of particularly tough and tetchy folk who lived in the now derelict stone cottages in the valley. As the story goes, someone saw Rabach kill a member of the group, forcing him to hide in a cave in the hillside to watch out for the gardai (police). Each of us in turn scrambled up the rocky and fern covered approach to the narrow black hole, the entrance to the cave. Each of us then squeezed through to the other side, except Donal, who declined for reasons of claustrophobia. ~ Monday. My first day behind the scenes at Mulcahy's Restaurant and Bar. I spent most of it standing in a corner of the tiny, frantic kitchen, watching mini towers of chicken, beef, fish and salad leaves being constructed at lightning speed then whisked out the swinging door. I saw fillets of lamb wrapped in pastry and artfully balanced on a bed of caramelised onion, nori-wrapped salmon oven roasted to perfection stuffed cod in a golden crust, crab patties with big chunks of real crustacean and a botanist's salad of crisp organic lettuce (three kinds) punctuated with exotic edible flora such as nasturtiums, borage and lavender. Bruce and his Australian girlfriend Ros had been to all the foodie traps in Sydney and it showed. Bruce even got me a white chef's coat and cap so I really looked the part. So eager was I to get my hands into the flour and fish fillets I agreed to make the daily eight loaves of house baked bread after just one day of observation. I went beserk and added sundried tomatoes, olive paste and herbs to the basic mixture. Unlike the resentment I experienced in my failed waitressing stint, my overenthusiasm was patiently welcomed by ever-striving Bruce, who simply pointed out where I was going wrong and basically left me to experiment, within reason. Lemon Tart: 5 lemons, zest of 2, juice of all. Somehow I read this as juice of 7 lemons, which explained the watery lake when I sliced into my first lemon tart. Bruce had mysteriously disappeared on this night, leaving Tommy the sous chef and me, the commis chef, to comandeer the gravy train. Fortunately it turned out to be a slowish night but it was busy enough for me, especially when an order for a 'taster plate' came in. This after-dinner extravaganza could well have been titled 'Death by Dessert', consisting of a miniature slice each of lemon tart, strawberry cheesecake, apricot cheesecake, a scoop of house-made ice-cream sitting in a tuille or sugar cup and a portion of chocolate fondant criss-crossed by white and dark chocolate sauce, all laid out on a longish oblong plate and dusted with ground pistachio nuts and icing sugar. An order for this buffet of sugar and fat made me break out in a cold sweat; no matter how I cut the slices they would wobble and break, and the ice cream would start to melt whilst the fondant was being zapped in the microwave. Actually, the logistics of this dessert seriously needed reviewing, because it meant running like a headless chicken between the freezer in the outside prep room to the fridge to the microwave and back again. "Ye should be able to turn 'round a taster in two minutes," said Tommy, dragging on his cigarette in the courtyard between orders. So somehow I had to slice three minutes off my best time, without throwing a wobbly. ~ My new little abode was a tiny upstairs room in a little cottage, sharing with Joanne and her hubby Kary. They were an odd couple; she a serious, cigarette-sucking and beer-drinking Irish country girl, he a gregarious, cigarette-sucking and beer-drinking Indian from Sri Lanka and a veteran of two civil wars in his home country. When I arrived home on this particular night Kary appeared in his dressing gown for a Harp (beer) and some craic (banter). He'd spent 18 months in the Indian Army at the front, pushing the Kashmiri border a couple of hundred feet back and forth. He tales of bullets whistling past his ears whilst he and his comrades chuckled over copies of old newspapers in the trenches, dragging pieces of his former best mate back into his hole and several miraculous escapes from guaranteed death left me wide-eared until 3am, and then fitfully dreaming about smiling, Harp-swilling people being blown to bits until my alarm rang at midday. "Tell you something", he said suddenly, and I knew I was going to be privy to yet another insight. "I knew all about you even before you moved in". He went on to explain how someone 'who would remain nameless' expressed alarm at the prospect of me moving in to their friend's abode. "She's useless, she got fired from Con and Katherine's, and besides, she's weird." It was at that moment that I got a sense of what is is to be a newcomer in a small town, with its inherent fear and loathing of anyone deemed to be left or right of dead centre. Strangely, this cheered me. To be an outsider, to not be accepted, to not 'fit in' is, for me, simply part of the experience. The experience of being a new, little fish in a new, even littler pond. ~ Generously, Bruce allowed me three consecutive days off to revisit a friend in Cahirsiveen, some 50 miles away on the farthernmost coast of the Ring of Kerry. Eddie was a birdwatcher I'd met several months ago whilst cycling from Tralee to Cork. For the first time in my life I was actually returning to visit a place I had passed through. This told me my life must be slowing down ever so slightly. Ros's sister gave me and my bicycle a lift as far as Caherdaniel, a spectacular spot 30 miles from Kenmare. Thus I had a chance to re-trace my tire tracks around this famous scenic drive. On the way I popped into Peter's Place in Waterville, where I had languished for five delightful days last November in the company of a traveller from Tennessee. Peter, a sprt 50-something looked even fitter than last year if that was possible, due to the physicality of building an additional 10-bed dorm at the back of his existing premises. No matter what time of day or night you land in this place there is always good craic; travellers from all over just seem to gel here, fuelled by the masterful craic of Peter himself. On this occasion I met an Aussie from St Kilda and a hyperactive young dude from Oregon travelling with his exact opposite, a laid back dude from a small island near Ontario in Canada. Ryan, the Canadian, confided that he found his erstwhile travelling buddy somewhat 'loud'. The loud lad, however, proffered some greatly detailed insights about the Czech Republic, well worth storing away for future reference. He also offloaded into my possession a 'France By Bike' book which did little to lighten his load - an entire pannier stuffed with a library of travel books, at which Ryan just shook his head. I rolled into Eddie's an hour later and one book heavier. Eddie was in good form, and the same as how I'd left him last - a huge ex-Englishman with a huge smile and a deadly sense of the craic. He had moved across the Irish sea to this little stone cottage in a wind-whipped and remote corner of Ireland, and was restoring the house and his sanity after suffering a big city, big business and big marital depression back in his home country. He told me how he would come home from his graphic design business in Manchester, lie on the floor and stare at the ceiling and not be able to move. He had gathered enough of his fading strength to get out of that life and start anew. We wondered just how many people in a similar predicament never muster the strength to make the jump. Eddie's life was very simple and nurturing now. He metered out his savings carefully, lived simply, and earned a little money from playing the baron or had drum in the Kerry Orchestra. The universe provides; the group had recently returned from a fully-sponsored trip through eastern Europe spreading a little Irish cheer. I admired his renovations, saying how impressed I was at people who knew how to build and restore houses. I said I would always worry that something was not quite square. Eddie pointed to where the dining room wall met the kitchen wall. "See that corner?" he said. "Probably not square. But…" he shrugged, "… it only has to last my lifetime". I remember how I obsessed I use to be over carpet colour and pleated shades during my nesting period some ten years earlier. At that time if you asked me what kind of house I wanted I would have answered in terms of architectural details - glass bricks here, a skylight there, a mezzanine floor with bed over looking the sunken lounge, a verandah. Halogen lights and slate walkways. Ask me now, and the vision is hazy; I can only say it would have to 'feel cozy'. "That's the hoogs you're missing", said Eddie. We spent the day dulling out together, eating Rich Tea biscuits and watching Father Ted reruns on video. We concocted a dire-looking supper according to a recipe of one of Eddie's fishing mates - a tin of tuna, Hellman's Blue Cheese Sauce, tin of baked beans, mashed potato and cheese all layered up in a bowl and microwaved. Anyone for seconds? The average man lives in a state of quiet desperation. Brendan Behan ~ I woke early and set off on a day ride from Eddie's place to Valentia Island, unreachable last November when I sat on the jetty with Matthew, the backpacker from Tennessee, our four eyes peeled for anyone in a boat who'd give us a ride. Not even a stick of driftwood obliged us. Of course I could have ridden over the ten kilometer suspension bridge way over there in the distance, but when you are with a non-wheeled companion, even temporarily, it puts the brakes on you. This time, no sooner had I rolled across the Portmagee Bridge than the Skelligs Experience Centre sucked me in. I was hungry, and the streamlined tourist-friendly café beckoned from within. I ordered and sat writing a postcard to Matthew, who had probably forgotten who I was by now. My soggy chicken and chutney toasted sandwich arrived with the waitress' apologies: "Sorry 'bout the top it got stook in the toaster". I eventually extricated myself from this bland watering hole and pedalled west for as far as the road would take me. The road became a rocky track, the ascended up a treeless hill towards the westernmost point in Europe, the Skellig Islands. As I came over the rise the sea unfurled before me, the coastline wending its way south in one direction and north in the other. Straight ahead were the magical Skelligs, two misty, craggy conical rocks jutting out of the sea like the tips of two ancient mountains, the words "Coney Island' and "Lost World of Atlantis" sprang to mind. Perched on the very tip of each was a sixth century monastry surrounded by raging seas. I left the bike parked near an old cement lookout tower and walked down the grassy slope to the very edge of the coastline and sat, staring out at this magical monastic retreat at the edge of the western world. I finally managed to tear myself away, climbed back up the hill to my bike, then road back through the centre of the island following a sign that said, "Ring of Valentia". All around lay open farmland, then suddenly, just near a turnoff signed 'To Chrlestown' I plunged into what resembled tropical rainforest flanking both sides of the road, dense and lush and not at all like the stark moors of the Ireland I knew. A long sweeping downhill lead me into Knightstown, the happening hub of sober Valentia Island. I cycled up to a phonebox with the intention of calling up Eddie to tell him to come on over and join me for a meal. Waiting outside the phonebox was a Chinese woman who introduced herself as Veronica, born in Trinidad, parents from China, married to an Irishman named Norm and living in Dublin. As I waited I tried to calculate the odds of meeting a Chinese Trinidadian in southwest Ireland but I gave up. I decided to take lunch at a quirky place called 'The Gallery Kitchen', cheffed by renowned local sculptor, Alan Hall. Alan is famous for his bronze statue of Charlie Chaplin in Waterville, where I had stopped to visit Peter's hostel. Apparently the world's most famous funnyman loved to unwind in the farthest place you could launch a scud from the USA. A glance around the restaurant revealed a cheeky piquancy in the chef-sculptor's art; directly opposite me hung a huge pair of pink plaster buttocks with legs splayed and a french baguette rammed home, captioned with a statement about French nuclear tests somehow being a 'pain in the ass'. Further along the wall a comical character stood frozen in time with a massive willy in hand. I turned to face a more appetising vista, the big oak dining table in front of me. It was just like the traditional formal dining table of my aunt, set with candelabras and fruit bowls and a big vase of flowers, and a glass top protecting a lace table cloth and photos below. My dinner company turned out to be three 40-something cyclists from the West Coast of the USA, touring the UK, France and Ireland according to the breakneck itinerary devised by the oldest of the trio. One of them, Dick, just happened to be riding the same bike as I, a Bike Friday New World Tourist. The meal was excellent home cooking, the kind I like to cook for myself, and I made a note to return to sample the entire menu. It is interesting that when presented with the chance to eat normal, home-cooked food, it is a delight, and we are even happy to pay for it. Standing on the other side in my commi chef's uniform, I would always think that if people are paying for food, it should be something innovative that they would never cook themselves. I made a note to suggest to Bruce we serve fish fingers with canned peas and instant mash, plus jello and tinned fruit for dessert and see how it sells. ~ I left Eddie's house at 8.30am and made it back to the kitchen by 2pm, just in time to be a half an hour late, to Bruce's slight annoyance. "I pay you to be here on time", he said curtly when I wheeled my bike into the courtyard. He was in the throes of lunch, with scores of orders for hamburgers and veggieburgers flying through the swinging door. He said he made little profit on this trade, but did it to keep up the goodwill. And in a two-street town with a lot of behind-the-hedges gossiping and undermining, and over ten restaurants vying for the picky tastes of the clientele, he needed all the goodwill he could get. That evening we got several orders for people sharing meals. This annoyed Bruce also. He pointed out that you cannot pay the rent and electricity on five people sharing a 6 dollar vegetarian pizza. I peeked out into the restaurant and sure enough, it was a group of cyclists. Bloody cheapskates. For the first time I was seeing it from the other side, whereas before I would think nothing of buying a half portion or sharing. Now I knew that it produced monumental groans in the kitchen. Much later I was to work in a mountain top hotel in Costa Rica with four rooms to rent. The tariff was $35 a double. A Dutch and German couple arrived, stared around the simple but cosy room and declared it a rip-off, pointing out that back down the road on the highway was a bigger room for $18. I pointed out to them that a hotel with a swimming pool is going to be more expensive than a hotel without. Here at Avalon Reserve, they could hike through 170 hectares of primary and secondary rainforest, or they could turn around and go stay at the cheaper hotel and walk up and down the road. At one stage I would have been them. And I would have turned around in disgust. I was learning about what it takes to run a business, because I had always been a salaried employee who couldn't care less about who paid the gas bill. It was a busy night, with every seat full until almost midnight, two hours past the official closing time of 10pm. Out the back, things were frantic. We would whip around the kitchen and out to the prep room at the back like dodgem cars, always mindful of the trecherous swinging door which had a tiny little window to warn of oncoming traffic. Salad leaves were flying everywhere. I now know never to enter a restaurant when it is full. If it is full, things are going nuts out the back. Whenever we were half full there was time to place a garnish without throwing it, serve a soup without spilling it, send out a salad without forgetting the dressing. After three months of tourist season Bruce gave me a raise from 80 quid a week to 100, in order to keep me on through to mid-September. I was already starting to experience a kind of burnout. I had wanted to know what it was like to work in food and now I was experiencing the downside as well as the upside. The upside is the creativity, and sheer delight in producing something scrumptious to the eye, nose and throat. The downside was that after the initial learning period wears off, you switch into machine mode, turning out the same thing day after day, night after night, always to he same precise standard, always in the same short time frame. I was also getting a touch of the old loneliness. After the nightly grind of cleaning up the kitchen, putting away all the food, and picking over any untouched dessert scraps that had come back through the door, I would return to my little cold room at around midnight, exhausted. Kary and Joanne tended to eat in their bedroom where it was warmer, there was a color TV and they could fumigate each other without bothering me. So quite often I was left loitering in the streets or in the house with no-one to talk to. One morning before my shift I happened to be gazing into the window of the local record and video store and suddenly saw the partial answer to my problem: a harmonica! It came with book and tape. I was so excited I took it to the restaurant to show the folks in the kitchen. "It's the lonely person's instrument," said Tommy. For three days my harmonica and I were inseparable. It took me about that long to discover how hard the darn thing was to play. In fact I spent a further three days trying to bend a note, and on closer examination of the book, I realized I had been blowing when I should have been sucking. Or was it vice versa? I was sitting on the front lawn before my belting out exercise three on the harmonica and watching Joanne transplant a rose bush when up strolled Alison, the woman I'd hostelled with in Dublin. She'd gotten me to this town in the first place, lining me up with my short-lived waitressing stint at the Italian restaurant in the Other Street. Alison was a wily Scot of indeterminate age who lived day to day and was hugely distrusting of the system. Consequently, she refused to sign anything that would give her any kind of ID. A mind as sharp as Bruce's favourite carver, she had completed an Economics Honours degree in her youth, bought some clothes and makeup for and interview, saw everyone else desperately doing the same, then summarily burnt clothes, books and piece of paper, and started living off the seat of her pants. To feed herself and her quest for total independence from the system, she had done just about anything and everything, including living off air for four years in a remote part of West Ireland. Her first job after destroying her degree was tutoring economics students by day, and by night, donning a 'tartie lettle skert' as a cocktail waitress trying to extract as much money from bored businessmen as their expense accounts didn't allow. Another time she worked in a pub making pies, where she spotted an ad in an old newspaper for writers for the Economist, one of Britain's most prestigious business magazines. She wrote to the editor explaining what she was doing, making pies, and what she would really like is a job writing for the magazine. She got an interview. She lost the job, she says, by failing the booze test - the editor managed to get her plastered on whisky proving that if she had to get her subject off balance using the age-old inebriation technique, she would be the one left under the table, sans the information the magazine had sent her to artfully extract. The editor's parting words, however, were, "Never change. Stay the way you are and you will go far". She had indeed gone far, at least when she owned a passport. She had hitched across America on no money, after blowing it in the first three weeks of a two month holiday. It was only then, she said, that the adventure really started. She gave new meaning to the notion of Scots being thrifty. She camped with gypsies. She got thrown out of a truck in the middle of nowhere when she refused to pay 'in kind' for her ride. But more often than not, she said she found Americans disproportionately helpful and caring about her plight. I suggested she write a book called "America on $0 A Day - Doing it the Scottish Way". She shook her head. "These memories are for my enjoyment and whoever I deign to share them with". Alison was someone I had absolutely no qualms hitching anywhere with. If anything, she should have had qualms about hitching with me, which is exactly what happened when we decided to make the most of my day off and hitch to Killarney, about 12 miles away. The weather was grand, perhaps a little too grand for what turned out to be a hot and completely unsuccessful attempt at getting a ride. We got as far as Kilgarven, the next town, and stood for over an hour in a truck layby lane in the blazing sun as carloads of tourists shot by behind tightly closed tinted windows. Alison, who had never failed to get a lift in her life, remarked that it was probably because there were two of us, and thought it an insidious reflection on the male race that a girl hitching solo is subconsciously seen as a potential shag, even in the deepest sinkholes of the mind of the most honourable male. Zoom, zoom. "Heard of 'extremist gardners'?" she remarked suddenly when the hundredth car had zoomed by and we'd run out of things to whine about. These, she said, were radical permaculturists who don't believe in digging, lest the 'lattice' that runs throughout the soil planet-wide is disturbed. Thus, "turning a sod out the back could give a sympathetically aligned gorse bush in Botswana an inferiority complex." "Oh really….". Zoom, zoom. ~ I turned 36 whilst sweating over the 15-second assembly of five organic salads, watching the precarious Chrysler Tower-like creations sail out the swinging doors on a waitress' arm and prayiing that they'd made a safe landing. Actually, there was no time to pray, an order for three taster plates, one nori rolls and a crab cake entrée were already pinned to the shelf. That morning I had woken early and pedalled down to Dromquinna, a romantically old stone restaurant and lodging house perched on sweeping grounds with dramatic views over Kenmare Bay. My intention was to hire a canoe and go for a birthday paddle. On the way I stopped at Nicky Ned's to collect one of their incomparable TLT's (toasted Turkey Lettuce and Tomato sandwich) and noticed a barefoot girl in hippie clothing eating bread from a huge bag in the trunk of a car. She was a wild-eyed drama queen from Australia; her partner in grime an ex-Eton ex Sandhurst escapee from the UK, who introduced himself as 'Brother Clear'. They lived on 123 acres about 25 kilometers down the road towards Sneem, living in a couple of caravans with their kids and growing vegetables and probably the odd interesting strain of weed. As she stuffed perfectly decent-looking bread and pastries in her mouth (they'd found the day-old stash behind the bakery on top of a skip) and hopped from this foot to that, she told me how she lived off a government pension of 70 quid a week even though she was a foreigner. How did she do it, I wondered. She explained that one day she was hitching and couldn't get a ride, so eventually she lay on the road until the cars had to stop. For this act of desperation she was hauled off to a mental hospital where the doctor deemed her insane enough to register for the lurk. For 70 quid a week, she seemed pretty sane to me. On coasting into Dromquinna I hired a canoe from Clive, whose girlfriend worked in the restaurant, and paddled out to a couple of little islands, past the odd seal or two bobbing in the calm waters. He came paddling up behind and we collected a bucket of mussels from the rocks around the island. In the distance I saw a man capsize where the water was choppier - I suspect he dug his oar in whilst trying to 'back' - memories of myself making the same mistake in a single scull prevented me from following suit. The owner of the property was a crusty old fellow who had made his billions selling $2 shop stuff, albeit in huge volumes. His eloquent wife Sue, on hearing that it was my birthday, presented me with a little gift from the business - a $2 all purpose carry bag set in three sizes, which turned out to be extremely useful when I finally laid down my apron. That time came a little more subtly but no less surely than my inauspicious dismissal from the waitressing job in The Other Street. First, my email would not send in the local Net Café called the Bean and Leaf, or the Lean Beef as Phillipe the young waiter use to call it. The owner, accomodating up til now with letting me use the computer for wordprocessing for free, asked when I would pay for the electricity. Further, I did not get served in the Horseshoe bar despite waiting until 11pm. It was time to go.  Looking like the washer upper in a Chinese chop house - it's a great leveler, this cooking gig ... I finished up at Mulcahy's a week after my birthday, older and wiser about the food business. I learnt three things: 1) After the honeymoon period, it is more fun to be outside the kitchen than in, 2) In a small town, you will never fit in, but that is part of the experience, and 3) never go into a full restaurant. Chances are, there's someone like me out the back waiting to forget the dressing on your salad….

One wonders in this place Why anyone is left in Dublin, or London, or Paris Where it would be better, one would think To live in a tent or hut With this magnificent sea and sky And to breathe this wonderful air Which is like wine in one's teeth John Millington Synge From the wall at the Barracks History

Centre,

Cahirsiveen

Copyright 2003 Lynette Chiang All Rights

Reserved. |